Riding through fear

When the pandemic struck, Norwegian writer, journalist and H.O.G.® member Mikal Olsen Lerøen took to his motorcycle to meet those affected across his home country

WORDS AND PHOTOS BY MIKAL OLSEN LERØEN

OPENING IMAGE BY PAAL KVAMME

ILLUSTRATIONS BY LINE MONRAD-HANSEN, RES PUBLICA, NORWAY

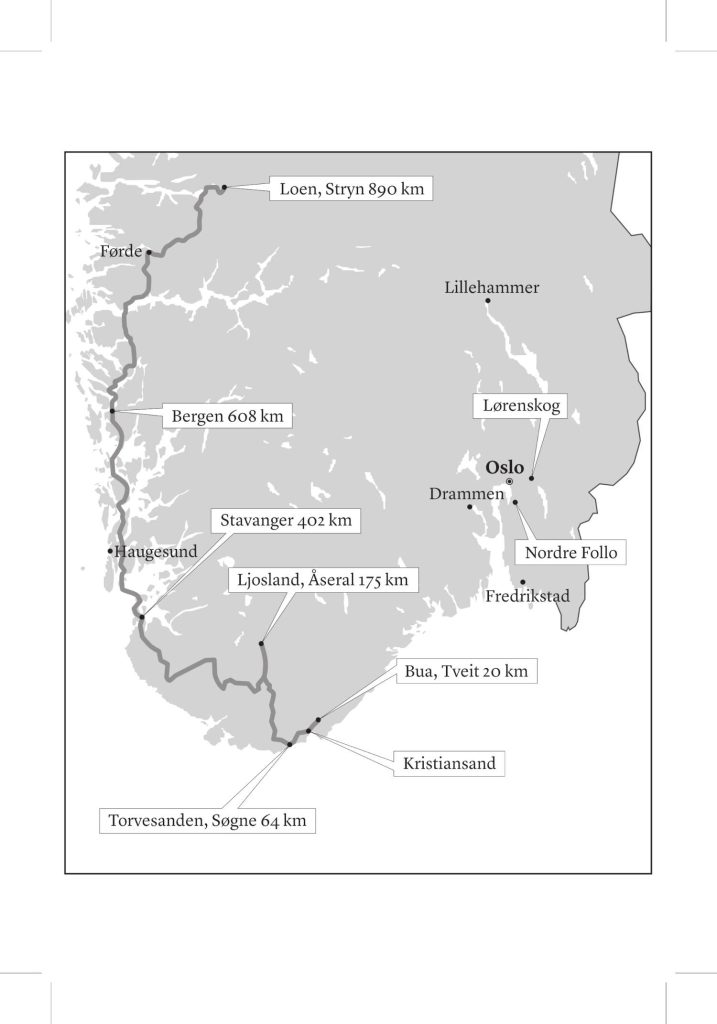

There’s always a moment before you make a big decision when you doubt yourself. At this particular moment, I was sitting in a beer garden in the southernmost part of Norway. The pandemic had just swept into the country, and I’d made a decision that would change the whole lockdown period for me. I was going to ride as far north in Norway as I could go.

My companion for the ride would be Castor, my grey denim Street Glide® Special, equipped with ape-hanger handlebars and a willingness to ride far. By meeting ordinary people, I hoped to keep my fears about the pandemic at bay.

SETTING OUT

Southern Norway is characterised by weathered mountains, warm fjords, beautiful roads that skirt alongside the rivers they follow inland and gentle people. As I shifted my bike down two gears and eased off the motorway, I noticed how tight my shoulders were. Castor was also grumbling reluctantly as the revs decreased and we rode gently alongside the fjord.

I cast my eyes down at the popular Hamresanden beach. There were people gathering along the waterfront, sitting far apart in small groups or paddling while observing social distancing. I shifted focus, taking in the view along the Tovdalselva River: winding, gentle curves between green squares and corn-yellow rectangles, as I passed by one farm after another.

KEEPING A DISTANCE

Being a biker, you might say I was already perfectly equipped for travelling through a pandemic. I was wearing long, padded leather boots over my biker trousers, and on top I wore an 8kg leather jacket, which felt bulletproof. Travelling at over 80kph through the countryside with Castor roaring like a raging bull made me feel I was putting some distance between myself and all the dangerous aspects of COVID-19 that we still knew so little about.

But what was it like for people whose job involved dealing with the public on a daily basis? In Stavanger, I was welcomed into a bar by Eirik, an optimistic 26-year-old bartender who would eventually be broken by the virus. During a year fraught with fear about the virus, finances and changes to the operating rules for bars, Eirik – the man who made Stavanger’s best Negroni – would be one of the many victims of isolation rules.

THE PAIN OF SEPARATION

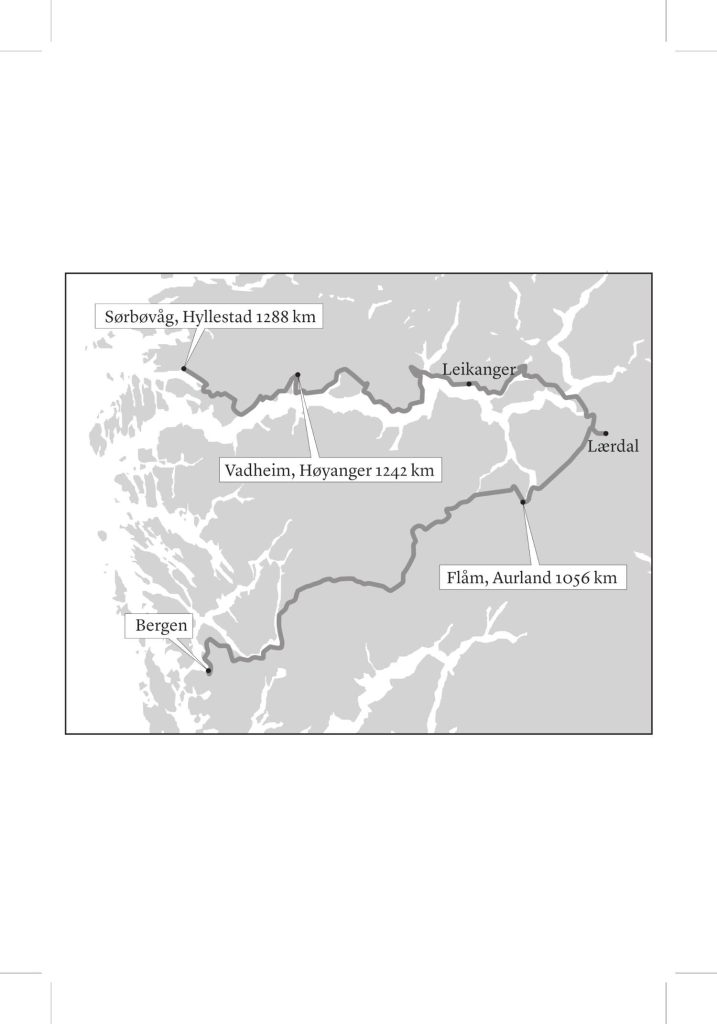

I drove inland from Bergen, heading for one of the world’s most beautiful fjords to meet one of the loneliest people in Norway. Åge was 69 years old and probably felt that time was running through his fingers like fine grains of sand. He was engaged but was more than 6,000 miles away from his fiancée, Mary. COVID-19 was going to keep him away from her for nearly three years. None of us knew if his love would survive during the pandemic.

I left Åge in the scenic village of Flåm in Vestland county and worked my way up through the gears, embarking on a journey through some of the most beautiful locations you can enjoy on a motorbike – the fjords of Sogn og Fjordane.

I took the ferry from Fodnes, near Lærdal, to Mannheller, passed Sogndal, and then it was as if I was involved in some kind of dance, with the sea leading and the road following. It led me through turns and around headlands, passing coves and long stretches where the sea crashed right against the mountain. Man and motorcycle paled into insignificance.

How determined does someone need to be to scrape out a life in the west of Norway? They’re tougher than the people down south. More stubborn, but quieter – perhaps because they know their words get blown away anyway. Here the roads are as thin as pencil lines drawn between the steep mountains and the deep sea. Every vehicle travelling along them is like a tightrope walker who mustn’t put a foot wrong.

BITTERNESS BREWING

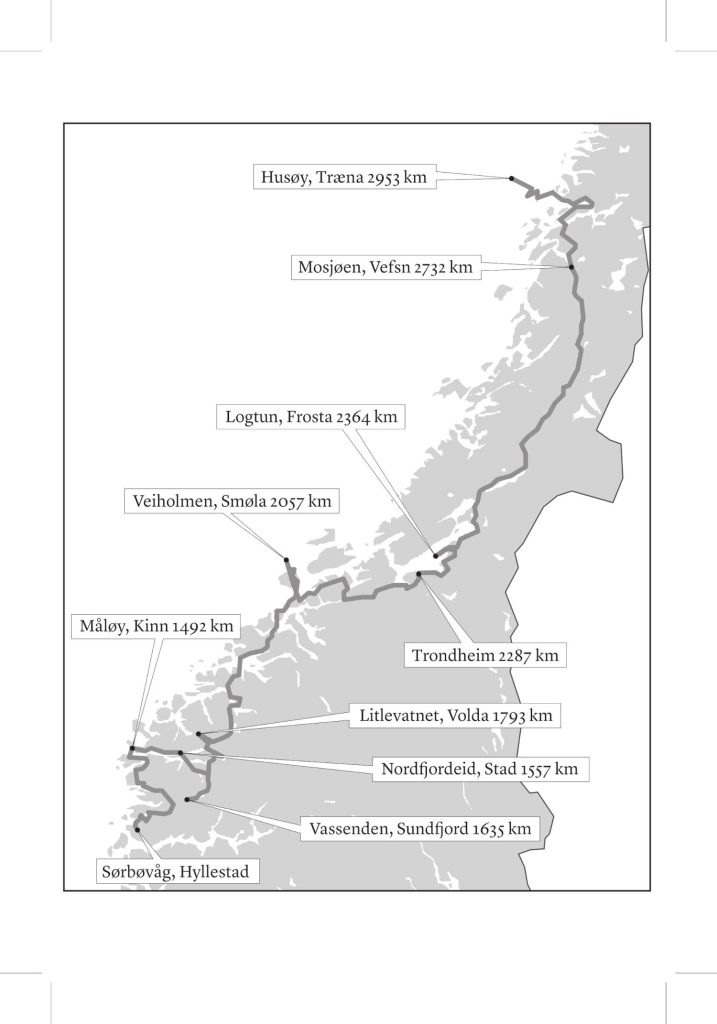

By now, Castor had covered 2,000 kilometres and I’d lost track of everyone I’d met. But I knew what they were wondering, here in the middle of Norway. The small communities were far apart, making it harder for the virus to spread. There was almost no sign of infection in Møre og Romsdal or the smaller places in Trøndelag. People felt it unfair that they couldn’t go out and exercise or go to school just because the pandemic was affecting major cities in the east.

NORWAY’S TUSCANY

Trøndelag is made for motorbike riding. The soft contours of the landscape, the round hills and the beautiful strips of dark tarmac criss-crossing lush valleys make it a kind of Norwegian Tuscany, and I was about to arrive at the heart of it, the beautiful municipality of Frosta. The road rose up over the Foldfjord, lifting my bike up above the blue expanse of salt water and affording a view of the mountains in front of me.

Castor and I were not suitably dressed for the occasion, but we celebrated Norway’s Constitution Day with a brave group of people who had chosen to isolate themselves from an early stage rather than waiting for government rules to come into force. Local council chairman, Frode, became the hero of the municipality when the council implemented these rules, just like Norway’s laws were first enacted here in Frosta 750 years ago.

DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVES

I was now on my way to a destination of hope, Træna, to meet someone who used the pandemic to do something positive. Sunniva was a 26-year-old woman who had taken control of her own life after becoming unhappy in her excessively small flat in an overly large city. She had upped and moved her ‘office’ to the idyllic island she came from, and now managed the accounts for several European departments of a Silicon Valley company from her room. Sunniva was one of many people who had used lockdown to reassess their values and wishes.

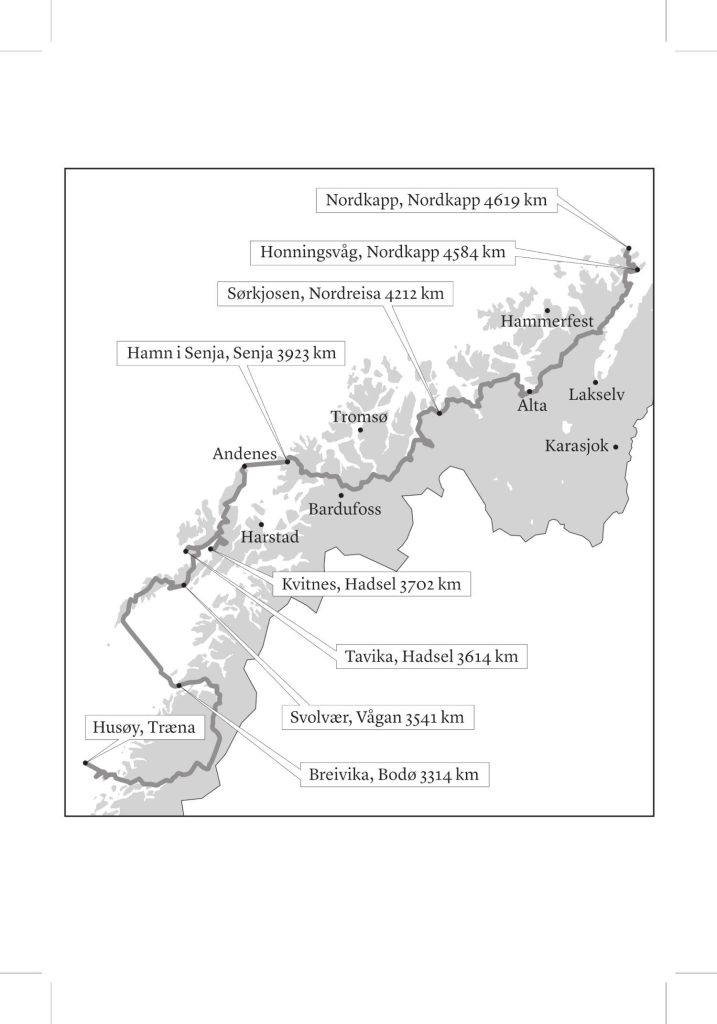

ENTERING THE ARCTIC CIRCLE

Finally, Castor and I arrived in the Arctic region of Norway. I had already ridden about 3,500 kilometres through this long country; nevertheless, there were still more than 1,000 to go before I’d arrive at the North Cape. And if you thought that up here a kilometre was equivalent to a kilometre anywhere else, then think again. There are seldom two-lane motorways or generous speed limits in northern Norway; you and your motorcycle have to fight for every mile, often riding along single-track roads that crawl and meander around inhospitable and brutal scenery.

Here, people are used to fending for themselves. So, when the chief medical officer in Hadsel municipality, Ingebjørn, discovered that Norway didn’t have a digital system for tracking the pandemic infection, he made one himself, which would become crucial to the country’s fight against the virus.

TOUGHENING UP

The next day, I chose to head east towards one of the finest fjords in the world – Lyngenfjord. In this location, people are more afraid of landslides than the ‘little devil’ of a virus that had by now paralysed the world. Statistics for the last 10 years reveal there have been 2,380 avalanches on Norwegian roads every year, which I didn’t want to think about. The weather had gone from bad to worse during the night, there was soil on the road surface, and in some places the water shot out at me horizontally from a small stream.

I was so cold that when I finally entered a hotel somewhere between Lyngen and Alta, the manager backed away.

“Is the bar open?”

“No, it’s not possible to serve drinks here now.”

“Because of COVID?”

He nodded.

“Sit down at the bar and I’ll put out some whisky and ice, then I’ll go for a walk and check if there are any windows open upstairs while you’re waiting.”

He smiled. I tried to smile back, but I couldn’t manage it.

Castor and I were getting ready for the last big stage of our ride. But the Finnmark region was so unrelentingly huge. And never had the distances felt longer than today. I refuelled in the town of Alta on a sleepy Sunday morning. No one here knew it yet, but the next day the city was going to be locked down. Over the next 48 hours, the chief medical officer would detect four separate, unconnected outbreaks of the infection. After filling up, I enjoyed a coffee in the sun. A little girl was discussing with her mother which ice cream to have – it was five degrees outside. I was among the toughest of all Norwegians now.

END OF THE ROAD

It is difficult to describe Honningsvåg as a pretty town. On the dock, I got talking to a tall man wearing a black docker hat and coarse gloves. He told me the story of the skipper who ran a ship aground right by the harbour because he and his girlfriend were having such a good time on the chart table. The dock worker finished his story by saying “in the end, we all die, right?” This is the extreme sense of humour, self-irony and toughness they have up north. Then he showed me his Harley®.

The road to the North Cape runs along the shore of Skipsfjorden.

It was the middle of June, yet there were large mounds of snow piled up along the hard shoulder. I passed a sign which warned that the next 28km would be dangerously gusty. The wind rocked Castor and thumped me on the shoulder.

This was where Norway ended, and I could not continue any further on my journey. I leant gently over the edge of the North Cape plateau and looked out over the open blue sea. Then there was an almighty bang and the breath was knocked out of me by a wind coming from below. Bloody hell! It was starting to snow.

I turned around, ran down to the car park and got on my bike.

But I couldn’t ride when it was snowing. My right thumb was still pressing the ignition button; the rumbling started below me. There was a Tom Waits song coming out of Castor’s speakers:

There’s a house on my block that’s abandoned and cold.

I started crying.

For two years and more than 4,600 kilometres, I had kept my fears at bay by riding on with Castor and meeting new people who had given me hope, ideas and inspiration to choose the life I wanted to live and not what society thinks is best. I felt like shouting, “Hey, COVID-19, you lose — eventually.” But yelling in an empty car park is worse than crying, so I’ll let Tom Waits have the last word.

What makes a house grand, ain’t the roof or the doors.

If there’s love in a house, it’s a palace for sure. ■

Tags:

Read more tales from the Harley Owners Group!

Croatian Sunshine

The 31st European H.O.G. Rally returned to celebrate under blue skies in Medulin from 12-15 June 2025

In the pink

Creative imaginations were let loose on a spectrum of Harley models, with the top entries showcased along the marina